Artist Haya Halaw and her family immigrated years ago from Syria to Jordan, where she stayed until she had to immigrate again to Germany. These forced migrations were accompanied by climate and environmental changes. Today, Halaw sits at her workdesk in Hamburg and reflects on these changes and their gender-related impact.

Every day, and every time we speak on the phone, my mother asks: “How’s the weather in Germany?” I reply: “It’s cold today, but no rain.”

And every time, her answer is the same: “There’s no rain in Amman either, and it’s so hot here.” We wonder together about how the weather has been changing over the past years. “Dear God, how are we going to live without water?” she laments. “There are so many water cuts in Amman.”

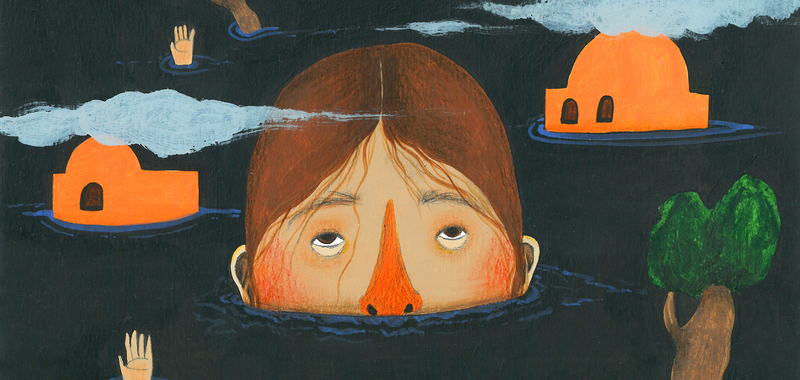

The most worrying thing is that this is just the tip of the iceberg, compared to what’s to come. My family and I, like thousands of others, had to flee Syria and take refuge in neighboring countries. So many of the people who ended up in refugee camps then found themselves at the mercy of natural disasters: severe snowstorms, floods, heatwaves, and other critical, sometimes life-threatening, conditions. The impact of these conditions is more severe on women and girls, who are still the most vulnerable groups in the midst of these crises. The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) estimates that 80% of those who have been displaced due to climate change are women, which makes them more vulnerable to violence, especially sexual violence.

“While they sleep, wash, bathe or dress in emergency shelters, tents, or camps, the risk of sexual violence is a tragic reality of their lives as migrants or refugees,” explains Michelle Bachelet, the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. “Compounding this is the increased danger of human trafficking, as well as child marriage, early marriage, or forced marriage, which women and girls on the move endure.”

While researching this piece, I discovered that the loss of biodiversity and the rapid climate changes—such as the warming of oceans, the melting of glaciers, droughts, floods, and forest fires—also have a negative impact on the girls and women who make up over 40% of the workforce in the agricultural sector. Land degradation will make it more difficult for these girls and women to access food, as well as water resources in some cases, thereby increasing the food insecurity gender gap, and leading to greater rates of homelessness and migration.

Will I be facing any of these climate disasters, I wonder?

Some of my most cherished memories are the times I spent during my adolescence in my mother’s village, Asila, during the olive and wheat harvest. I remember my family gathering around the fire and the table, after a long day in the fields. The fragrance of firewood remains with me. I miss my mother’s village, where my relatives and I would steal green almonds and cherries from the orchards every summer. We would hang out by a spring, listening to the sound of frogs and enjoying the shade of a giant willow tree. The spring has dried up now. I don’t know what has happened to those fields and orchards, to that willow tree. Armed militias took control of the village and its surroundings.

Today, I sit at my worktable in Hamburg, observing the many signs of climate change and the different birds that come to rest near my window.

I see nature as an extension of myself; I’m deeply affected by its fluctuations. Its warmth and springtime make me happy. I observe the details of the natural world with wonder. I go out every day to the parks near my home in Hamburg, and I listen with joy to the symphony of sounds all around me: wind teasing the leaves, trees breathing in the air, birds chirping, water flowing, rain falling, shoes crunching on the snow...

Nature is where I rest from work, where I take walks to rid myself of the episodes of anxiety and panic, where I find peace and reassurance. Many girls and women did not have these experiences. I was, and still am, one of the lucky ones. I did not lose my home when the earthquake struck the north of Syria last February. I did not spend years of my life without a safe home. I have not faced sexual harassment or violence. I learned to swim with my uncle in the village, and I’ve never experienced a flood. I was and still am one of the lucky ones, until now.

_________________________________

Note: This article was produced in cooperation with the Heinrich Boell Foundation, Middle East Office. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views or positions of the Heinrich Boell Foundation, Middle East Office.

Add new comment